Ballistics

What goes up....must come down. So much for gravity.

In tennis this passes for a deep concept. Many players still think that if you aim a hard-hit ball at a target that is one inch over the net strap, it will always end up somewhere in the opponent's court. This instinct is, of course, wrong. Most balls aimed at that point will fall short and end up in the net. If you are standing behind the baseline and hit a ball from waist high that barely passes over the net at the peak of its flight, it will be out over the baseline about four feet (neglecting air resistance). Most players don't know that if you hit a ball at knee height hard enough, it has no chance of finding the other court, but the same ball hit at waist height will be well in. Add aerodynamic considerations of drag and spin and whoah...you got some complex stuff going on. If you care about what happens to the ball after it bounces - and you really should - it is a bit too much for any of us.

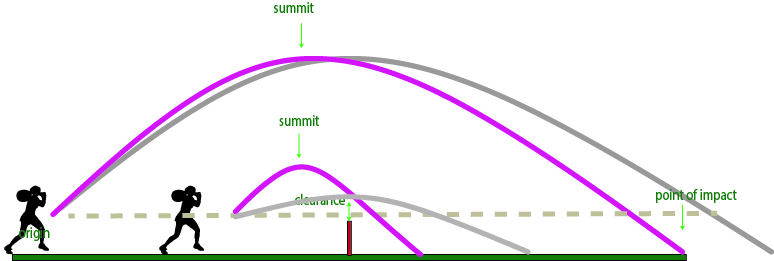

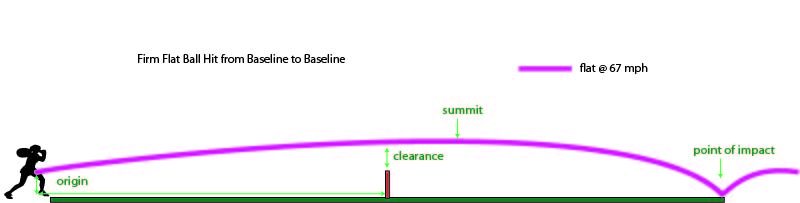

The basics of projectile motion are summarized in Fig. 1. You make contact with the ball at some point in space - the origin. The key parameters of the origin are its height above the court surface and its distance from the net. The ball then sets out for a point some distance above the top of the net strap, but of course, gravity is pulling the ball down so it never actually reaches this point. That is a problem for a lot of people who think that aiming the ball at a point 3 feet over the net gives you three feet of clearance.

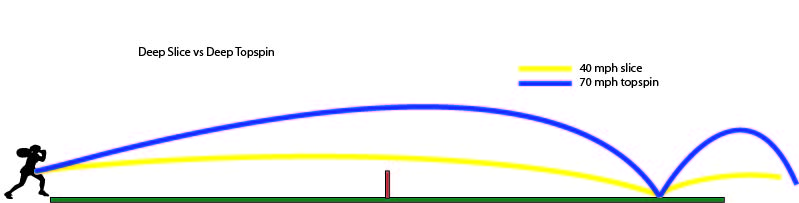

The actual clearance depends on all sorts of factors as anyone will tell you who has tried to hit an oh-so-safe high puffball and had it dribble into the net. It would help our feeble brains to estimate clearance if the ball reached maximum altitude - the summit - as it passes over the net, but it seldom does. The summit is important, however, because it is key to both clearing the net and hitting a certain area of the opponent's court, but more on that later. After it reaches the summit, the ball starts to come down, but seemingly faster and at a sharper angle than it went up. As a result, the "court distance" between the origin and the summit is sometimes greater than from the summit to the point where the ball reaches its starting height. The reason for this has to do with air resistance. This drag force pushes back on the ball as it flies through the air and it increases with speed so that at 20 mph the drag force is half the force of gravity and for a serve, at 125 mph it is seven times the force of gravity! Because the air drag slows the ball, it does not fly as far before gravity pulls it back to its starting height. That is why the ball appears to "crater" at the end of its path. Topspin increases this effect, and underspin decreases it. (Fig 2.)