The Basic Foundation of ALL Tennis Strokes

As different as serves, volleys, groundstrokes, lobs, overheads and drop shots may look, they are all means to the same end - to hit the ball over the net and into the box as far away from your opponent as possible. We would also like to put as much unpleasant "stuff" (spin, depth, pace, high or low bounce) on the ball as we can - anything that will frustrate and infuriate our opponent. The tool we have to work with is a high tech, carbon fiber, perfectly balanced weapon of war.

The Goals and objectives of all tennis strokes include the following:

- Return the ball to the opponent's court safely inbounds.

- On this all depends. The preceding is pointless without achieving this so...

- There is no negotiation with this point. You NEVER tolerate lower percentage on a shot to achieve power, spin or placement. Not never! On the other hand...

- Perfect consistency is impossible, so the trick is to manage your percentages.

- On this all depends. The preceding is pointless without achieving this so...

- Confound, confuse and contort your opponent with:

- Placement (to forehand, backhand, behind your opponent - NOT at the lines.

- Spin (topspin to send the ball high, slice to keep it low, and side-spin to drive them crazy. In this context effective spin is called "weight" as in "Wow, she hits a heavy ball!"

- Depth as defined by where the opponent has to stand to address the ball, not where it bounces. A heavy, hard topspin on the service line is a deep ball while a floaty slice that drops 3 feet inside the baseline is nothing but a short approach about to be transformed into a fuzz sandwich for the approacher. Hitting deep means hitting a solid ball with pace and lots of spin halfway between the service and baselines for consistency.

- Have fun!

- This can be challenging if your are constantly mortified by your own unconscionable errors, but then that is the point of all this jibber-jabber. If you can't get your game to the point that egregious errors are the jocular exception instead of the cruel rule, then why hurt yourself? Take up running instead.

Tennis Good

Tennis is a blast - full of drama and comedy. You don't have to be top ten in the world to truly experience and enjoy it. If you know tennis and know yourself you can perform well beyond the limits of your God-given inabilities.

The Four Fundamental Objectives

An effective strike of the ball must result in four basic outcomes:

- Address the ball.

- get the ball into the strings

- Take control.

- change the direction of the ball

- Add pace.

- at least enough to get it over the net

- Add spin.

- reshape the flight path of the ball

- make the ball bounce funny

The Four Fundamental Objectives

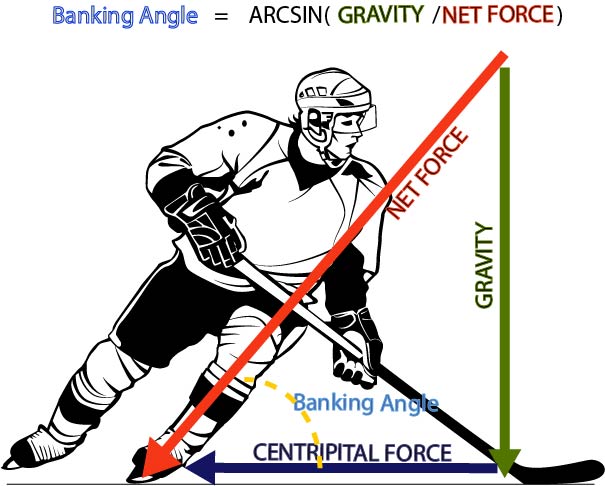

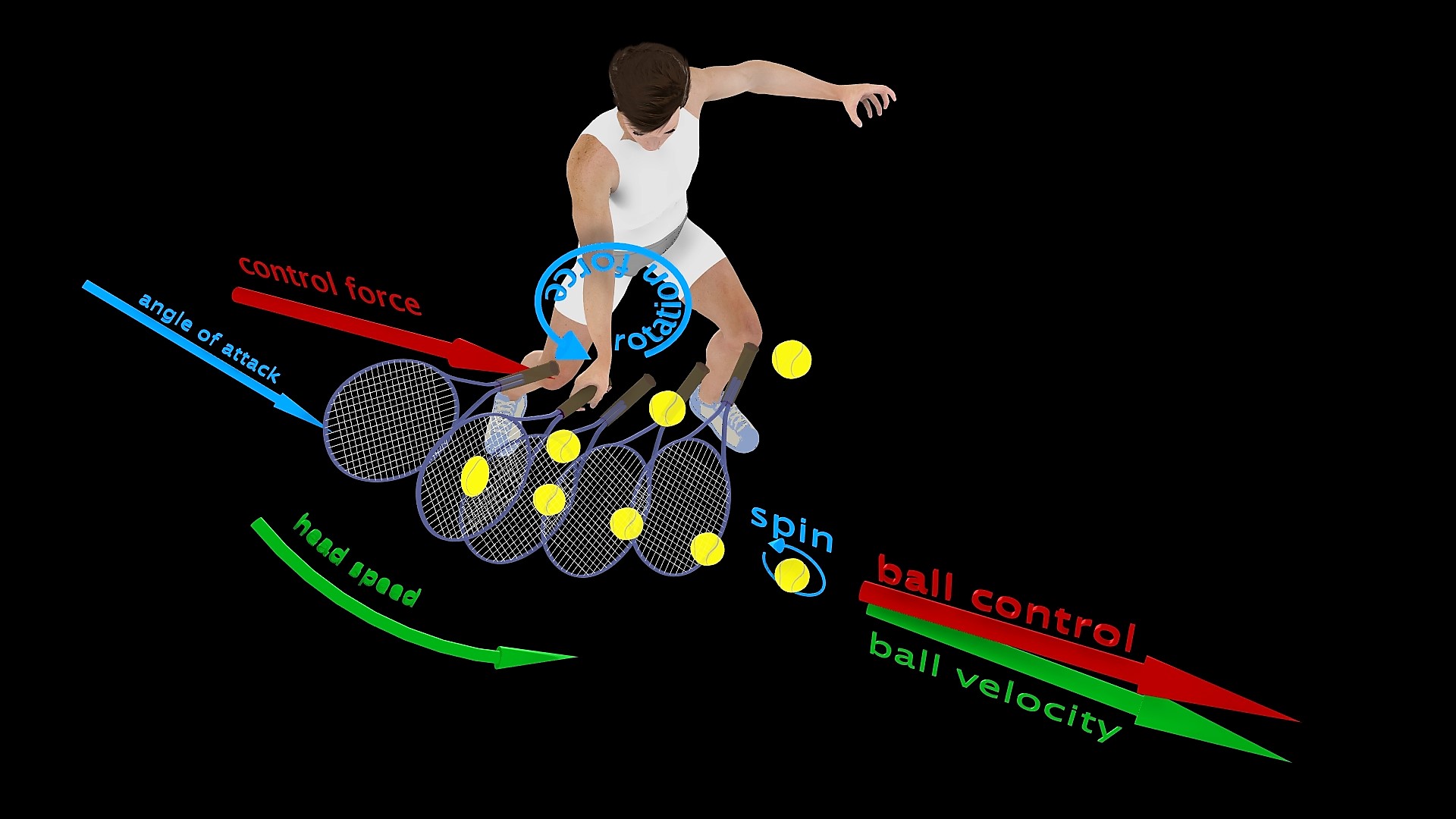

The trick is that you have accomplish all of these with a single swing and in a very narrow window of time - the five milliseconds that the racket is in contact with the ball. Moreover each these effects requires either a force or a racket movement in a unique direction (see figure below). If there is one reason why talent matters, it is this seemingly impossible task.

Moment of Contact

We develop the stroke foundation from the inside out beginning at the instant in time when the racket makes contact with the ball. The interaction between the racket and ball lasts only about five thousanths (.005) of a second during which time a racket travelling 90 feet per second moves about six inches. In that brief moment, you need to deliver pace, impart spin and, most importantly, take directional control of the ball. Let that sink in for just one second.....