How to Hit the Topspin Forehand

Time to transcend the general principles of ball abuse. While those principles apply to all players and all strokes, what follows is a prescription for how you should hit a topspin forehand. This prescription is not the only, or even necessarily the best, way to hit a ball. Still, it does represent a specific technique that I have carefully tested, simplified, and tailored for the less-than-gifted. But this forehand is not a baby stroke. This chapter describes the most efficient use of snap, leverage, and balance to create professional-level control, pace, and consistency.

A Violent Beginning

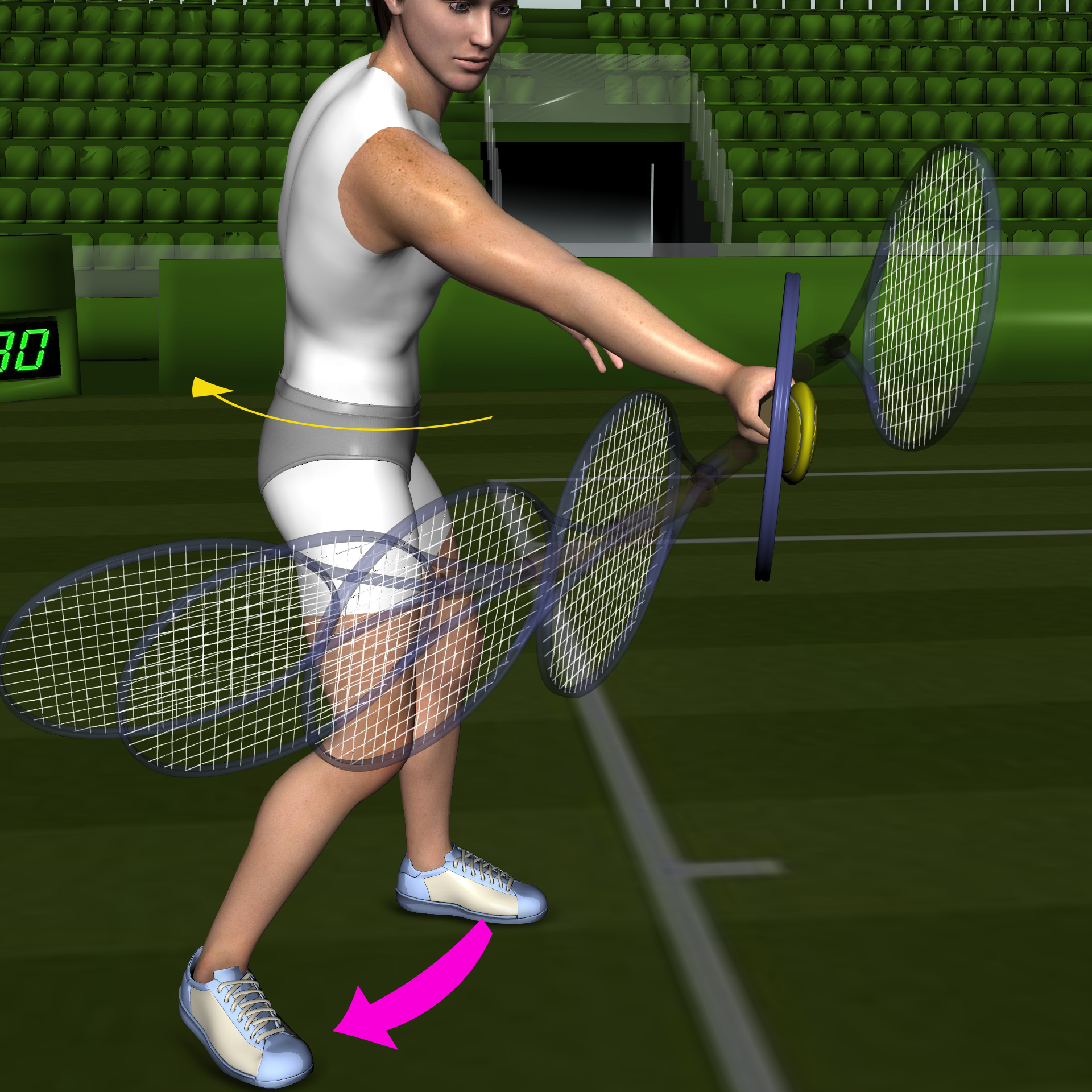

The Topspin Forehand (TSFH) unit turn is the transition from running or standing to hitting. Assuming you are a right-handed player beginning with weight on the RIGHT foot, you step into a semi-open stance with the LEFT foot. Pushing back with the LEFT foot powers the counter-rotation of the hips, shoulders, arms, and racket. As weight is 'loaded' back onto the RIGHT foot the counter-rotation slows and the pose is established. You straighten and lock the elbow in the pose and lift it high and away from the body. You should feel that you are backing away from the ball's flight path, giving the ball ample room to get by you. Your forearm should be moderately pronated, but the racket head above the wrist. The wrist is radial-flexed (cocked) so that the racket head is in front of the wrist. The positional relationship between the racket head and the wrist is critical. The pronation and cocking of the wrist put the racket head in position to properly 'wind-up' the forearm muscles when you start your forward hip and shoulder rotation.

An early, quick, and violent unit turn is the secret to 'quick hands'.

Note that counter-rotation does not necessarily stop, but it should slow down enough to allow the ball to reach the entrance to the strike zone. Conversely, if a run is required to reach the ball, the unit turn begins early in that run, and then you should approach any ball with the racket in the pose position. An early, quick, and violent unit turn is the secret to 'quick hands.'

RIGHT HANDED PLAYER!

- Unit Turn to Pose

- footwork

- ..starting from weight on the RIGHT foot

- step into a semi-open stance

- step FORWARD and LEFT (45 degrees) with the LEFT foot

- starts the unit turn

- step away from the ball's flight path

- don't crowd the ball

- loads the LEFT quadriceps muscle for balance

- bend the LEFT knee!

- hips and shoulders

- rotate together as a UNIT

- 15 degrees (short stroke) to 45 degrees (long stroke)

- QUICK and VIOLENT

- = 'quick hands'

- rotate together as a UNIT

- hitting arm

- elbow up and away from body

- EXTEND elbow

- for leverage and power

- to avoid shanks, misshits and loss of snap

- feels like reaching for the ball

- forearm mostly pronated

- racket face almost parallel to the ground

- for storing topspin forces

- fully cocked

- racket head forward of wrist (radial flexed or cocked)

- for storing control forces

- non-hitting arm

- supports the throat of the racket as long as possible

- locked, extended elbow

- assures hitting elbow stays straight

- reach across the body

- assures adequate hip/shoulder rotation

- reach across as if to 'catch' the ball

- helps keep focus on the incoming ball

- encourages hitting from hips, not arm

Extending the RIGHT elbow is essential for both power and control. By increasing the length of your arm you massively increase leverage which is the key to optimum power. Try shadow stroking with elbow straight then bent and listen for the difference in sound of the racket head swishing trhrough the air. A bent elbow massively increses the degree of freedom of movement of the forearm which makes consistency nearly impossible. A crooked elbow feels 'more free' but adds nothing of value to any stroke.

The LEFT arm's participation in the forehand is manifold, but the key addition is to force you to counter-rotate your shoulders and hips instead of bringing the racket back from the shoulder. The former is correct, the later a disaster (see 'Zone of Experience'. One way to remember to reach across the body with the non-hitting hand is to pretend to prepare to catch the incoming ball with the LEFT hand.