Control

How come talented players never seem to miss the sitters? Sitters are the great levelers of tennis. Anyone can, in theory, put away a shoulder-high volley with a minimum of muss, fuss or technique. You generally have a whole court to hit into and lots of choices on how to win the point. About the only incorrect choices are to drive the ball straight down into the base of the net or to float it over the baseline; over that immense expanse of open court that yawns before you. So why do talent-plus players usually choose correctly and you usually flub it? These are the unconscionable errors that starve your victories, infuriate and embarrass you to death. The talentoids also seem to hit everything else more consistently than you despite your superior stroke mechanics and unmatched desire to win. How do they pass you over and over by just sticking out their rackets? How do they reach behind themselves on overheads and hit well-placed winners? Why don't they bunt their groundstrokes over the baseline as you do on every other attempt? It isn't because they are hitting the ball softer; you have tried moon-balling or pushing the ball many times, and it reduced your percentages. So what is the deal?

The "deal" is control. A-players know how to inject directional control into every ball, and it is always a priority second only to putting the racket face on the ball. This mysterious power to control their shots is why their reach shots, trick shots, and half volleys, despite the lack of mechanical advantage, are often their best-placed shots. It seems that the more anxious they are about getting to the ball the more conscientious they are about injecting control. In that way, control is simultaneously an offensive and defensive weapon: Its a twofer! Beyond that, the mechanics of control are (almost) completely occult, so control is the ultimate stealth weapon! Anyone who has faced a player who seems to be able to completely and unexpectedly change the direction of the ball to their advantage knows how magical control can seem.

The Foundations of Control

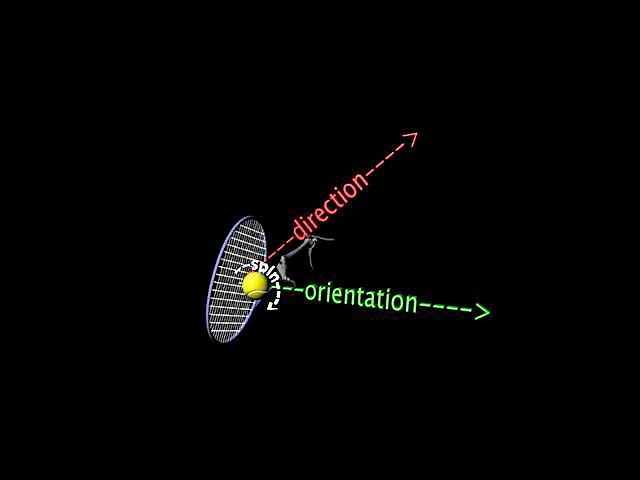

If this is the first article you have read in this site, you might be surprised to hear that the physics around control is based on the idea of impulse. Otherwise, I bet you saw that one coming a mile away. Anytime you want to influence the direction of the ball you must use impulse. Impulse itself is invisible and occult. The general feeling behind impulse is called "snap" and the only visual manifestations of snap is the sound of the ball coming off of the strings and a secure, solid feeling in the hitting arm. If there is a lovely, lively, musical ping or pop as the strings meet the ball, you have created impulse and taken control over the direction of the ball. "But how do I determine the direction the ball will go?" you demand, intelligently, to which I quip "Usually anywhere but the base of the net or the back fence is good!" By which I mean anywhere but where the ball itself wants to go by virtue of its incoming direction, speed and spin because when an undisciplined ball hits a moving racket, bad stuff happens. Just getting the ball turned in the general direction of clearing the net and avoiding the sidelines is a start. Staying inside the baseline is a bit trickier, but if we can take care of the most egregious errors, then that last can be greatly improved with the addition of spin to the ball. Indeed, the addition of spin turns out to be one of the foundations of control but not for the reason you might think. The way that spin changes the flight path of a ball is important, but not the primary reason for adding spin. The act of adding spin to a ball makes directional control possible through the geometry of spindirection.