Air Supremacy - How to Hit the Overhead

A-players don't miss their overheads. They miss groundstrokes, volleys, drop shots, serves... but not overheads. Why not? Is it because overheads are so easy to hit? Permit me to chuckle. Overheads are actually very challenging, so the pros must practice them constantly. They start young practicing thier overheads because, at some time in thier lives, they were humbled by the lowly lob.

Lobbing is easy. It is the least athletic of all strokes. No net to worry about, no need to hit hard or place precisely; yet a lob can be quite deadly. After having been burned a few hundred times by lobsters, it is no wonder that talented players devote so much of thier early careers to cultivating thier overheads. It may seem paradoxical, or downright stupid, to waste practice time on a stroke that one hits once or twice in a match, but if you show your opponent a weak overhead you will soon get a stiff neck from looking up. A player with with a reliable overhead rarely needs to use it. It is the ultimate deterrent to the lob. To master the overhead is to achieve absolute hegemony over a hugh volume of air over the court, denying your opponent the use of every qubic foot of space above your shoulders.

Smash vs High Volley

These two strokes are so tangled up with one another that I have decided to present them together. The high volley is the short stroke version of the overhead while the smash is the long version. The overhead boasts a long lag phase and a slightly longer follow-through than the high volley, so the overhead is capable of more raw power. So why not crawl under every high ball and hit it as a smash? The high volley is both massivly less tiring than the smash and offers more precise ball placment, so although the smash is more impressive, the high volley should be thought of as the go-to tool for defending your airspace. The smash is the stroke of last resort; reserved for those lobs that soar beyond the reach of the high volley.

The priority of defending the air-space does not end at the service line. In this age of heavy topspin, a popular tactical tool is to use high bouncing balls to erode one's opponent's power and consistancy. It is difficult to hit a shoulder high ball with a clean groundstroke, especially a two handed backhand. Instead, utilizing high-volley technique will permit you to handle high-bouncing balls safely and effectively with no muss or fuss.

Follow-Through to Perfection

The indisputable key to success at hitting both the smash and high volley is the follow-through. Proper follow-through virtually guarantees a solid, reliable overhead stroke, and failure to follow through properly is almost always disasterous. The 'subkeys' of the overhead follow through are as follows:

- Compact in Space

- stop the arm and racket

- creates the 'Explode' phase

- delivers conrol forces via 'impulse'

- stop the arm and racket

- Prolonged over Time

- keep elbow up for several milliseconds

- prevents collapse of the hitting arm

- misshits

- lost power

- netting and moonballing

`

- prevents collapse of the hitting arm

- keep elbow up for several milliseconds

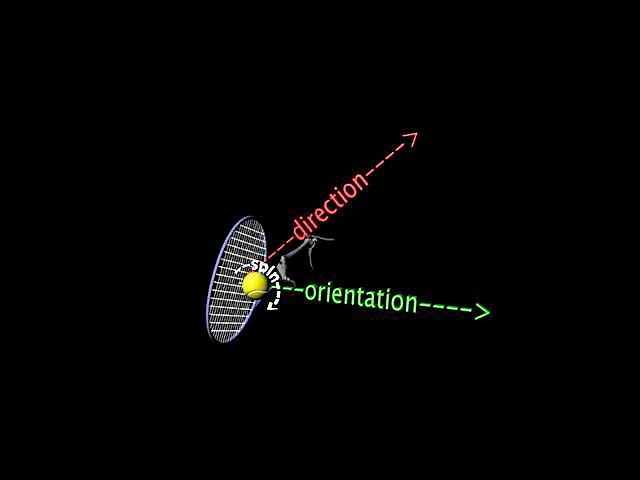

These subkeys apply equally to both the smash and the high volley. In fact, the only difference between the follow throughs of these two strokes is the pose one holds for a few milliseconds at the end of the stroke. In the high volley the racket is vertical with face is slightly open to the target, similar to the mid and low volleys while in the smash the racket finishes pointing down at a 45 degree angle and the face is severely closed relative to the target. The difference arises from the spindirection at the center of each stroke: The high volley is a slice, while the smash is a topsin similar to the serve. The smash ulilizes pronation to deliver power originating in the legs and conducted vertically through the body and arm to the point of contact. The follow-through on the smash is nearly identical to the service follow-through, excepting that the hurry-up nature of the smash means less time and loss of balance that tend to make one want to pull the arms down prematurely. Indeed, both the smash and the high volley, like all work done over ones head, are exhausting which can encourage an over anxious 'recovery', making one pull ones arms down prematurely. This can result in misshits and loss of power and control transferred to the ball. One may even find oneself adjusting the point of contact downward resulting in net balls, moon balls (as one lays the racket face back to compensate) and a significant loss of reach on the smash. To counter the tendency to pull one's arms down one must keep the elbows up and 'strike a pose' at the end of the follow-through for several milliseconds longer than one might for a normal volley or serve.