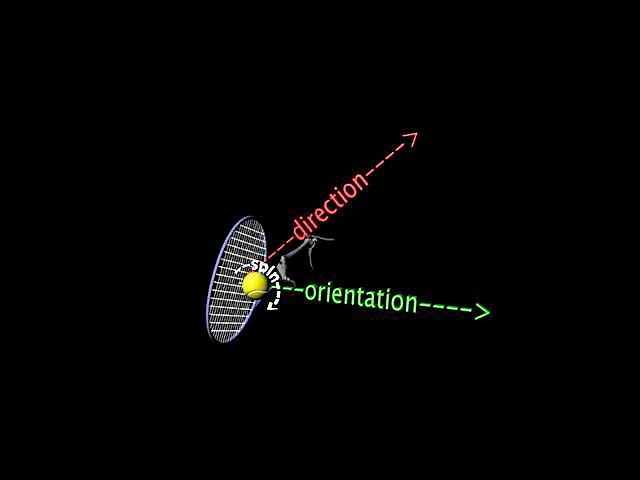

Spindirection

NEVER hit flat!

I think we are done here.

I could stop right there, and anyone who takes that admonition seriously will markedly improve their consistency and power. Sadly, some people (like me) need to know the whys and wherefores or they will misinterpret and misapply such an admonition.

First the 'wherefores'; When I say 'never' hit flat, I mean NEVER HIT FLAT! Not on first or second serve, not on the volley, the overhead, the lob or drop shot. Watch the pros. They put spin on everything. Even the "squash shot" - the shot that all of the pros use when they track down a wide ball - is all slice.

The 'why' requires a bit more elaboration. Fundamentally we are all trying to strike the ball in such a way that it lands on a target in our opponent's court. It makes intuitive sense to guide the ball along a straight line path to the target, but there is a net in the way. There is also, thankfully, gravity so we can hit the ball up to clear the net and it will then dive into the court hopefully onto the target. Therefore controlling the depth of the ball means aiming for a target above the net; not too high, not too low. Avoiding the alleys is different - that is more or less a straight line deal, but let us put that aside and concentrate on controlling depth because that is way more complex and difficult.

So as beginners we were taught to swing low-to-high, guiding the racket head along a straight line path that connects the point of contact (POC) to the target hovering over the net strap then follow-through the ball on the same straight line path towards the target, in essence guiding the ball along. This 'push' stroke is taught to every kid that picks up a tennis racket. We were assured that, should we mistime the ball a little, keeping the racket on the ball's intended flight path will give us the best chance of a successful strike. Eureka!

If this is the be-all, end-all of hitting a tennis stroke, why do all of the pros end up their strokes with their rackets wrapped around their necks? Or behind their ears? Why does the pro volley follow through go across the body? And what is with that corkscrew hitting motion that typifies the pro serve? Why not just slap that sucker? The answer is that as endearing as the old follow-through-the-ball admonition is, it just doesn't work. Period.