Fed-style Topspin Forehand

The topspin forehand is the second most important shot in tennis. You might be able to win a match without one, but you won't enjoy it. The topspin forehand is the swiss army knife of tennis strokes. It can hit winners from the service line and passing shots from behind the baseline. It is offensive and defensive at the same time. It is, at once, the most natural and most complex way to strike at a ball so, more than any shot in tennis, it is the best friend of the more-talented and the worst enemy of those of us who are less-so.

The topspin forehand seems to be quite simple and natural for those with plus-sized talent which is remarkable given the complexity of the stroke. There have been many variations of the stroke over the years. Champions have been crowned with forehands comprising a variety of grips, backswings, follow-throughs, and stances. In recent years the stroke has evolved towards a common form that pros have optimized for the professional game. As recently a 10 years ago there were still two common styles of topspin forehand )as brilliantly analyzed by Christophe Delavaut) dubbed the "ATP-style" and the "WTA-style". Not wanting to be justifiably accused of sexism, and in recognition of the fact that most of the women in the WTA nowadays use the so-called ATP-style forehand, I will redub them the Fed-style and the Borg style. There are so many differences between these two styles I have chosen to deal with them in different chapters - as though they were two species that evolved separately, but my treatment belies the truth: The Fed-style is the ultimate evolutionary expression of the forehand. It represents a hybrid of the old eastern grip-style forehand of Rod Laver and John Newcomb and the semi-western/western grip style popularized by Bjorn Borg. The Borg style forehand is easier to teach and to learn than the Fed-style but it is less versatile and powerful. The Fed-style forehand is as complicated and difficult to learn as the kick serve, but the payoff is the potential for a 100+ mph groundstroke with tons of control and topspin to keep the ball in play. It is also easy on the arm and gobs of fun to hit.

Foundations

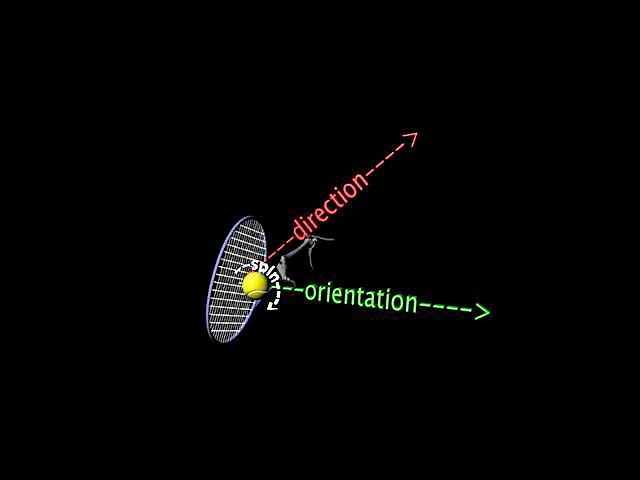

Allow me to confess a touch of childlike awe when I watch Roger Federer crunch a topspin forehand. I am blown away by the enormous arc of his backswing, the intricate flip of the racket as it starts forward, the left arm reaching across the body as if to catch the ball out of the air, the astounding racket head speed and the long, collapsing follow through. The grace of the stroke, its mind-bending complexity, the power without effort and spin without contortion all conspire to evoke a sense of magic; that somehow Roger has transcended the bounds of science and reason. Of course, the always suspicious adult in me at first assumed all of these things are mostly the flourish of an accomplished magician. Meer showmanship, perhaps with a touch of misdirection lest some talented up-and-comer figures out the trick and turn this formidable weapon against him. Of course, my instincts, as per usual, were pathetically wrong on all counts. Federer's forehand is not a magician's illusion. The entire stroke reflects bedrock principles of physiology and physics. Every facet of it contributes to power, control or spin. There is real magic in it; components that are important but completely invisible to the naked eye, even when viewed using high resolution, slow-motion video analysis. It is an understanding of these invisibles that allow us to make sense of what is going on in in the Federer-style topspin forehand. It turns out that they are the basis for all excellent tennis strokes and apply widely to sports as disparate as hockey, golf and ping pong.