Consistency - the Elusive Hobgoblin of Tennis

In the end, consistency is the impossible dream of tennis. The ungettable get - the holy grail - the end of the rainbow. Let's face it, you can have the best forehand or serve or volley in the world, but if you can't manage to put it in play twice in a row, you lose.

Even the pros cannot avoid errors. Some of those are "forced errors" due to an incoming shot hit with amazing pace, spin or placement, but many are the same kind of knucklehead boners you and I hit.

Without errors, tennis would not exist as a sport. Imagine points that last hours - who would have the patience to watch, much less play? In the '70s there was a real fear that women like the unflappable Chris Everett, would destroy women's tennis by systematically eliminating unforced errors. It didn't happen. Even Chris sometimes netted the easy volley.

So, if we cannot eliminate unforced errors we should at least strive to minimize them if only to save wear and tear on our egos, rackets, partners and the ears of anyone within earshot.

The key, we are told, is to play the "percentages". That means getting the ball in play as high a percent of the time as possible. But if hitting 0% errors is impossible and 49% is not worth the bother, then what is the goal? How do we define consistent play? The answer is as simple as the question - consistent play is the play that wins. Remember that your goal is only to win. Most of the time you only need to win 51% of the points to accomplish this, and you can win those points as ugly as you like - there is no bonus for the cross-court screamer that skips off the edge of the line. The puss-ball that flutters and bobs its way to the "T" and induces your opponent to drive a forehand into the center of the net wins the same number of points - namely one. As a result, consistency depends on the shot you are hitting. For an outright winner, finding the court 51% of the time is a winning percentage. You have to hit one in a row. Maybe not all of your shots are outright winners. Perhaps you more commonly just hit groundstrokes deep and down the middle waiting for your opponent to make an error. In that case, you need to hit 4-8 in a row to win 50% of the points, but the math is interesting. If you can hit 4 in a row and your opponent can only hit 3, you will win all the points. More realistically on average, you might miss 20% (80% consistency) of the time while your opponent misses 25% of the time (75% consistency) then every time you hit the ball you have a 5% better chance of getting the point. Overall you will win 55% of the points which means you ALWAYS win!*

I think you can agree that consistency is good and the more, the better, so how do we maximize our percentages. Step one, of course, is to fix any bad physics and bad psychology in your game through study and practice, practice, practice. That, believe it or not, is the easy part. It is also insufficient because you once you know how to hit the ball and have some modicum of control you have to figure out where to hit it. Picking a target is the part that always stymied me. I would take the advice of my mother and others that one must hit the ball deep. THAT was the magic formula of success in tennis- just hit the ball deep and don't miss! Don't under any circumstances hit the ball hard, just hit it deep. Hitting deep means hitting for the baseline, and just over the baseline is one of those places that is "out". The closer you hit to the baseline, the more likely your ball will be out. Unless you can reliably drop your ball onto a target the size of a basketball, balls hit near the baseline will be out at least half the time. Can talented players hit the ball that accurately? Can they even control the pace, spin and flight path of the ball reliably enough to keep balls from straying long? What about hits that are off center verses right in the sweet spot of the racket face? How does one anticipate and accommodate so many random variables and still drop the ball reliably on such a small target?

No, there is no way that even the most talented player can hope to reliably control the ball to the extent required to aim just inside the lines and keep the ball in play. The truth is A-players all know the most important secret of tennis; that nobody is that good.

So where do the pros and other gifted ones aim the ball? What does it mean to hit the ball deep? The solution is so simple that I feel deep shame that it took me half a century to figure it out.

A-players don't hit for lines, areas, baselines or sidelines. They don't just try to clear the net with plenty of topspin and hope the ball hits the ground before it crosses the opposing court's boundaries. A-players aim at very specific and very small targets - they shoot for a point the size of a baseball then expect and count on not hitting that point. That's right; they don't actually hit their targets. They are humans, and they know it. They also understand (intuitively) the concept of Circular Error Probable or CEP.

CEP is a concept that became important during the cold war when the US needed to know how many nuclear warheads they would have to stockpile and mount on missiles to balance the threat from the Soviets. At its peak in the mid-'60s, the US had 30,000 warheads in its stockpile compared with less than 5,000 held by the USSR. By 1990 the US had reduced its stockpile to 23,000 while the Soviets increased theirs to 40,000. The US felt they didn't need as many warheads as the Russians because our Circular Error Probable- the radius of a circle around a target that would contain 50% of the actual hits aimed at its center - was half the size of the Soviet's. Therefore they needed only one quarter as many warheads to assure the destruction of a given target.

CEP is an essential concept in tennis. For a given player, stroke and situation it tells you where the balls are likely to land relative to where you want them to land. The CEP in tennis is much more of an ellipse than a circle. The long axis of the ellipse is oriented along the line of flight of the ball, a reminder that it is much harder to control the depth of a ball than the placement side-to-side. The pros' Elliptical Error Probable (or EEP) is slightly smaller than those of us mortals, but the important advantage that the pros have over us is their acceptance of their inherent inaccuracy and how they manage it.

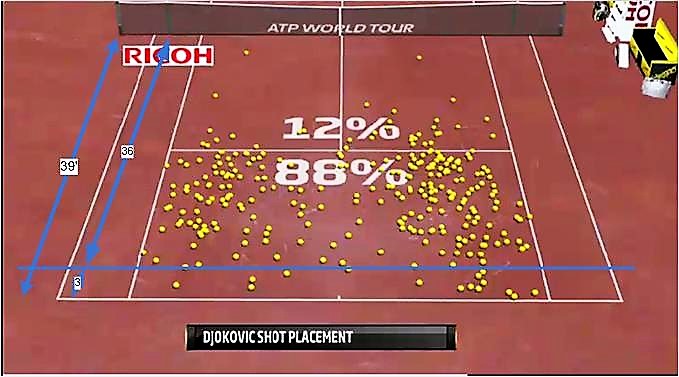

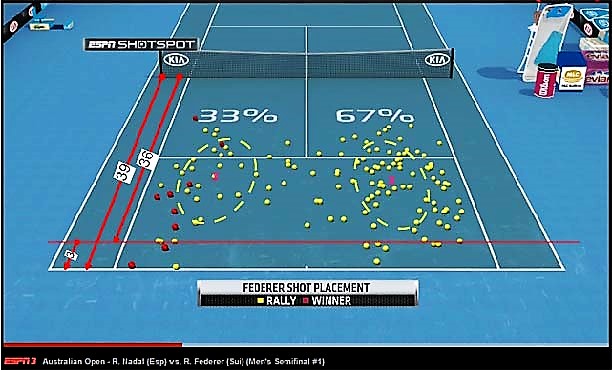

In a normal baseline-to-baseline rally, A-players hit for a spot about halfway between the baseline and the service line, an area called the back-court. If we divide the back-court into two boxes side-by-side and refer to each of them as the ad (opponent's left) and deuce (opponent's right) backcourts and look at where the pros hit (see Figures 1 and 2), we discover that the pros don't aim for lines at all. They aim for a point near the center of the deuce or ad backcourts. If you examine the "splash pattern" of shots on the Shot Spot images and assume the actual intended target lies at the center of this distribution the actual target point seems to be a few feet closer to the service line than to the baseline. The balls land in a random pattern that outlines two elliptical areas, one on each side of the back-court. Some of the balls bounce near the target points (pink X's in Figure 1) while others are quite short, actually bouncing in the service boxes and a few fall close to the baseline. If a ball hits any line it is not the product of genius ball control and amazing technique; it is luck. Note that the vast majority of the balls pros hit fall within the inbounds area - they achieve this by allowing for a large margin of error at all times and on every shot. They are not satisfied with 50% of their balls landing in; they want 75-80%. Also note that the CEP is more elliptical than circular, so in tennis, let's call it an EEP or Elliptical Error Probable. The elliptical distribution of the hit points is interesting because depending on where you are standing when you hit the ball your target point's relation to the baseline and sideline will be different. Hitting up the line, you can aim pretty close to the sideline but should aim halfway between the service and baselines, but when hitting cross-court, the ball should be aimed at a point more inside the sideline but a touch deeper and closer to the baseline. Either way, your target should be well inside of the baseline and sideline.

The randomness of this technique is difficult to fathom. We are used to our heroes "going for the lines" and hitting them at dramatic moments of the match, bringing people to their feet in convulsions of adoration and delight. We assume there is some divine inspiration or magic that guides the ball to the line at those critical moments in the match when only a winner will do. In truth, it is just pure luck. If the pros could reliably hit a line by aiming at it, why wouldn't they do it every time?

* OK that is a lie. There is a little thing in mathematics called "Simpson's Paradox" that is a statistical quirk in tennis that can allow a player to win the majority of the points and still loose the match. Federer has the dubious distinction of leading the field in loosing matches notwithstanding winning a plurality of points.