The Power Wave

The concept of a power wave in tennis is designed to counter the widely held belief that, as athletes, we are nothing but a bunch of rods and levers motivated into action by the sequential contraction of our muscles. There is truth in that belief, but it cannot begin to explain the beautiful miracle of a well-hit topspin forehand, nor the horrific spectacle of a shoulder-high volley dumped into the base of the net. For one thing, the mechanical model of tennis stroking does not account for the expression of the stroke over time. We don't push off with our feet at the same moment we strike the ball, luckily, since our brains could never handle performing that many tasks at once. Indeed, the only way to accomplish something as complex as a tennis stroke is to generate the energy in our feet early in the stroke then transmit or propagate it through time and space via the medium of the body and ultimately to the racket and ball. Along the way, various parts of the body harvest energy and momentum from the wave, converting them into ball control, spin and pace.

The Shape of the Wave

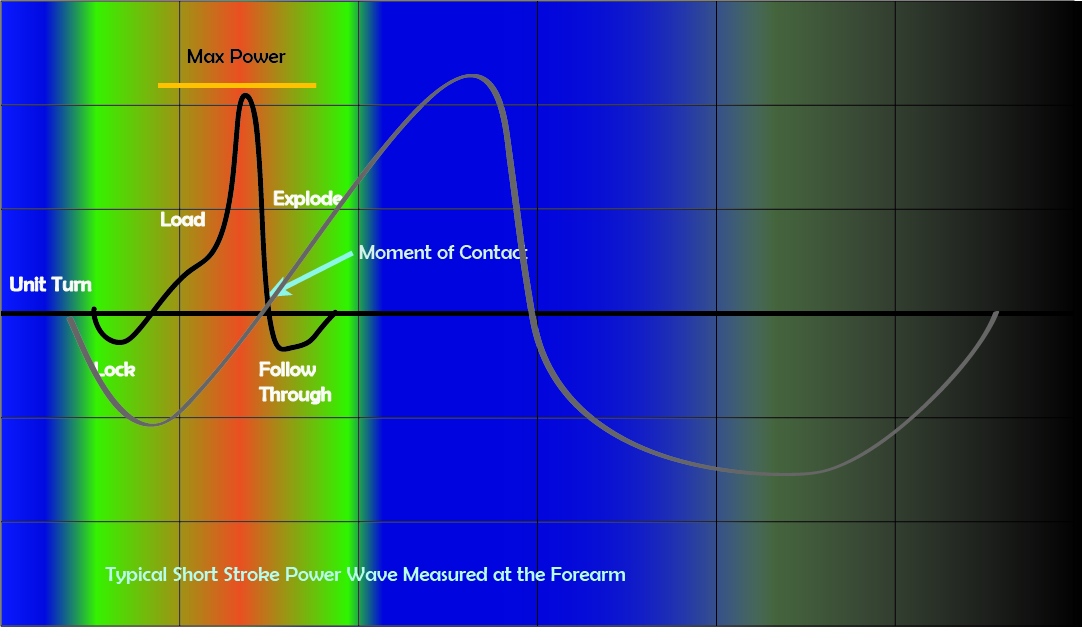

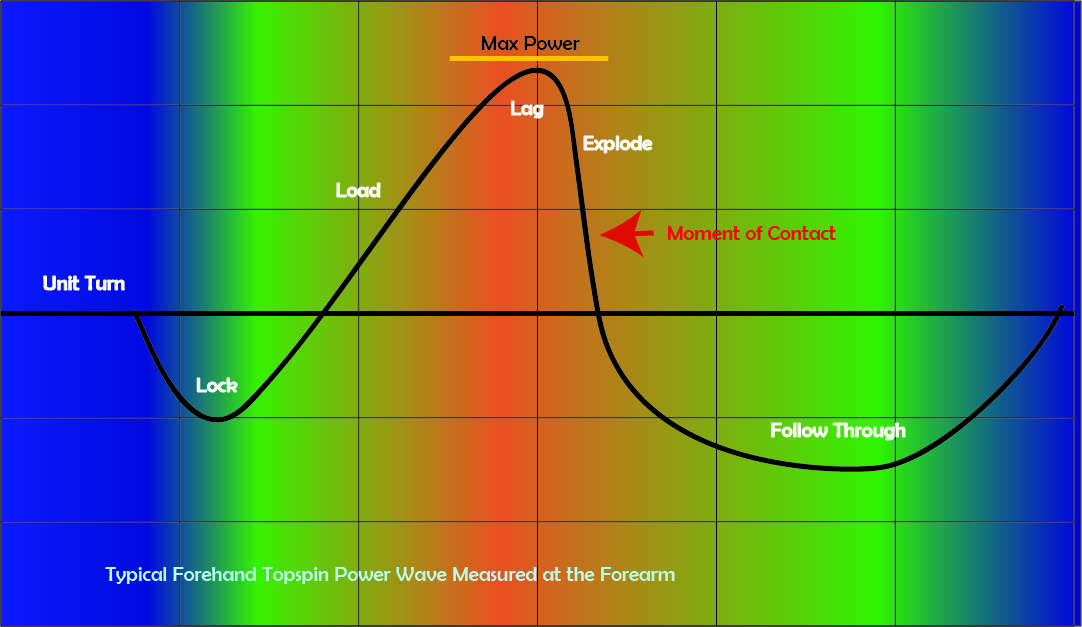

When we conceptualize a wave we like to take a tracing over time as in the diagram above. The horizontal axis represents time, while the vertical axis represents directional power. (Physicists will balk at this notion as their concept of power has no direction. Tennis players will understand this concept. Power in the positive direction is power directed towards the target. Negative power is in the opposite direction, i.e., in the direction of the backswing.) Imagine a sensor on the player's wrist that measures the forces trying to displace it. At first, the force is backward, dragging the wrist and racket away from the ball. This move is the lock, an essential component of every stroke from the drop shot to the serve and typical of wave motion which is always too and fro, forward and back or up and down. Suddenly the power changes direction towards the ball starting the acceleration forward.

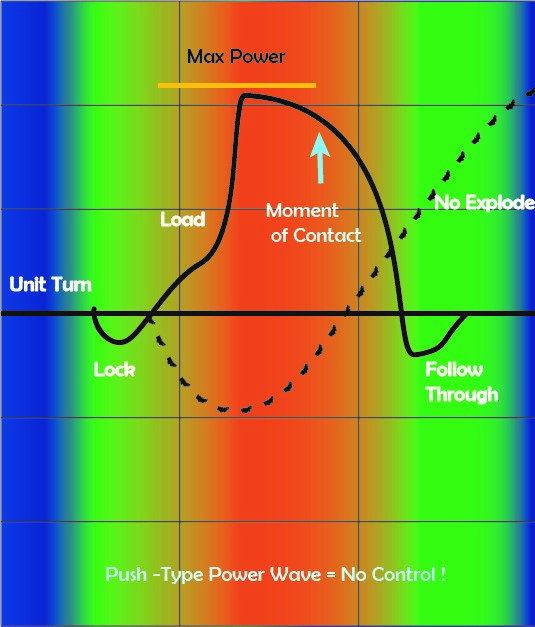

At this point the racket flips, loading stretch shortening forces into the forearm which will ultimately be injected into the ball as impulse for spin and control. As the power wave continues to crest, the racket is dragged behind the wrist - accelerating and building racket head speed for pace - the lag phase. Suddenly, at the peak of the wave, the power reverses, and the shoulders start decelerating. The racket head's inertia allows it to catch up with the wrist, releasing the stored forces into the ball. At the moment of contact with the ball, all power neutralized, and there is no force on the racket coming from the shoulders. Eventually, the wave becomes completely negative, keeping the racket from wrapping totally around the player's neck. It is important to remember that the lower body generates the power wave - a conspiracy of the feet, legs, and hips. Although you can add power to the wave using your upper body, that can be a dangerous procedure. In particular, at the moment of contact power delivered through the shoulders should be zero, not positive, lest one misdirect the ball away from its target by injecting impulse in the wrong direction (see Push Syndrome).

Back and Forth

Every shot in tennis starts with the racket moving away from the oncoming ball. I call this move the lock or "backswing proper" to differentiate it from the unit turn - the larger and more ostentatious component of the backswing.

Every shot in tennis starts with the racket moving away from the oncoming ball.

The lock, like every component of every stroke, requires a source of power. That power comes from an initial reverse-rotation of the hips as you transfer bodyweight from the front foot to the back foot.